Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) is a vital protein involved in cell growth, proliferation, and tissue repair. Its significance extends from fundamental cellular processes to its role in cancer progression and targeted therapies.

In this blog, we’ll explore the functions of EGF, its signaling pathways, and its clinical implications in medicine.

What is Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF)?

Definition of EGF: What it is and Its Role in Cellular Processes

Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) is a small protein that plays a critical role in regulating cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation. It belongs to the family of growth factors, which are molecules that bind to specific receptors on the cell surface to trigger intracellular signaling cascades.

EGF primarily acts by binding to the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), a transmembrane protein with intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity. This interaction activates a series of signaling pathways that control various cellular processes, including cell survival, tissue repair, and organ development.

EGF is especially important in epithelial tissue, where it stimulates cell division to repair wounds or replace damaged cells. Beyond normal physiological processes, its overexpression or dysregulation has been implicated in cancer development and progression, making it a critical focus of oncology research.

Discovery and History: Key Milestones in EGF Research

The discovery of EGF dates back to 1959 when Dr. Stanley Cohen and Dr. Rita Levi-Montalcini identified it while studying the salivary glands of mice. Dr. Cohen isolated EGF and demonstrated its ability to stimulate the growth of epithelial tissues. This groundbreaking work earned them the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1986.

Since its discovery, research on EGF has expanded, uncovering its critical role in cell signaling and its implications in various diseases, including cancer. The identification of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) in the 1970s further revolutionized the field, as EGFR was found to be a target for therapeutic interventions in cancer.

Structure and Properties: Protein Structure, Receptors, and Ligands

EGF is a polypeptide consisting of 53 amino acids, with a molecular weight of approximately 6 kilodaltons. Its structure is stabilized by three disulfide bonds, which are essential for maintaining its biological activity.

The primary receptor for EGF is EGFR, a member of the ErbB/HER family of receptor tyrosine kinases. EGFR is composed of three main domains:

- Extracellular Domain: Responsible for binding EGF and other ligands such as transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF-α).

- Transmembrane Domain: Anchors the receptor to the cell membrane.

- Intracellular Tyrosine Kinase Domain: Initiates intracellular signaling cascades upon activation.

When EGF binds to EGFR, it induces receptor dimerization (pairing of two receptors) and autophosphorylation, activating downstream pathways like the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways. These pathways regulate key cellular activities, including division, migration, and survival.

In addition to EGFR, EGF interacts with other members of the ErbB family, such as HER2 and HER3, under certain conditions. These interactions broaden its functional roles and significance in both normal physiology and disease states.

Functions of Epidermal Growth Factor in the Body

Cell Proliferation and Differentiation: Role in Tissue Growth and Repair

Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) is a key regulator of cell proliferation and differentiation, particularly in epithelial tissues. By binding to its receptor, EGFR, EGF activates signaling pathways such as MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT, which promote the growth and division of cells. This function is critical in maintaining tissue homeostasis by replacing old or damaged cells with new ones.

In addition to its role in normal cell turnover, EGF also influences cell differentiation, enabling cells to acquire specific functions necessary for tissue development and repair. For instance, during embryogenesis, EGF contributes to the development of organs by guiding cells to form specific structures.

Wound Healing: EGF’s Role in Regeneration and Epithelial Repair

EGF is essential for wound healing due to its ability to stimulate the migration and proliferation of epithelial cells. When an injury occurs, EGF is released at the site of the wound to accelerate the repair process. It promotes the formation of granulation tissue, enhances keratinocyte migration, and facilitates re-epithelialization—the process by which the epidermal layer of the skin is restored.

Additionally, EGF helps modulate inflammation by reducing excessive immune responses that could impede healing. This dual role makes EGF a promising therapeutic agent for treating chronic wounds and burns, where natural healing processes may be impaired.

Angiogenesis: Promoting New Blood Vessel Formation

EGF plays a significant role in angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing ones. This is particularly important in situations where tissues require increased blood supply, such as during wound healing or tissue repair. By activating EGFR and interacting with other signaling molecules like VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), EGF promotes endothelial cell proliferation and migration, key steps in the formation of new blood vessels.

While this function is beneficial for tissue repair, it also contributes to pathological conditions like cancer. Tumors exploit EGF-induced angiogenesis to create a blood supply that sustains their growth and facilitates metastasis. As a result, therapies targeting EGF and EGFR are being developed to inhibit angiogenesis in cancer patients.

EGF Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms

EGF-EGFR Binding: How EGF Activates the Receptor

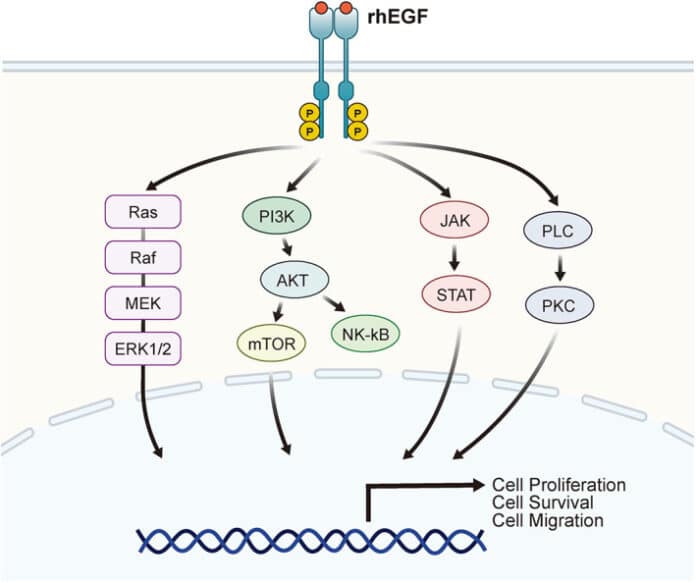

The signaling process of Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) begins with its binding to the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) on the cell surface.

When EGF binds to the extracellular domain of EGFR, it triggers receptor dimerization, where two EGFR molecules pair up. This dimerization activates the tyrosine kinase domain, leading to autophosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues on the intracellular domain. These phosphorylated residues act as docking sites for various signaling proteins, initiating multiple downstream pathways that regulate critical cellular processes.

Key Pathways

- MAPK/ERK Pathway (Cell Proliferation)

The MAPK/ERK pathway is one of the primary signaling cascades activated by EGF. Once EGFR is activated, it recruits adaptor proteins such as Grb2 and SOS, which subsequently activate Ras, a small GTPase. Activated Ras triggers a kinase cascade involving Raf, MEK, and ERK.

ERK, the final kinase in the pathway, translocates to the nucleus and regulates the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation and differentiation. Dysregulation of this pathway, such as overactivation of Ras or EGFR, is commonly associated with uncontrolled cell growth in cancers.

- PI3K/AKT Pathway (Cell Survival)

EGF also activates the PI3K/AKT pathway, which plays a critical role in promoting cell survival and preventing apoptosis. The binding of PI3K to phosphorylated EGFR leads to the production of PIP3, a lipid molecule that recruits AKT to the cell membrane.

Activated AKT phosphorylates multiple downstream targets, promoting cell survival, growth, and metabolism. This pathway is frequently dysregulated in cancer, often due to mutations in PI3K or loss of PTEN (a negative regulator of the pathway).

- JAK/STAT Pathway (Immune Regulation)

The JAK/STAT pathway is another downstream signaling route activated by EGFR. Once EGFR is phosphorylated, it can activate Janus Kinases (JAKs), which, in turn, phosphorylate STAT proteins.

Phosphorylated STATs dimerize and translocate to the nucleus, where they regulate the expression of genes involved in immune responses, inflammation, and cell growth. This pathway contributes to immune system regulation and is implicated in inflammatory diseases and cancer when aberrantly activated.

Dysregulation in Diseases: Oncogenic Pathways Involving EGF

Dysregulation of EGF signaling is a hallmark of many cancers. Overexpression of EGFR, mutations in its tyrosine kinase domain, or continuous activation of downstream pathways can lead to:

- Uncontrolled Cell Proliferation: Hyperactive MAPK/ERK signaling drives excessive cell division.

- Enhanced Survival: Aberrant PI3K/AKT activation prevents apoptosis, allowing tumor cells to evade cell death.

- Angiogenesis and Metastasis: EGF-induced signaling promotes blood vessel formation and tumor spread.

These dysregulated pathways are targets for therapies, such as EGFR inhibitors (e.g., gefitinib, erlotinib) and monoclonal antibodies (e.g., cetuximab). By blocking EGFR or its downstream signaling, these treatments aim to curb tumor growth and improve patient outcomes.

Role of EGF in Cancer Biology

EGFR Mutations in Cancer: Common Mutations

Mutations in the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) are frequently observed in various cancers and are a major driver of tumor development. These mutations lead to constitutive (unregulated) activation of the receptor, even in the absence of EGF binding.

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): Activating mutations in the EGFR gene, such as exon 19 deletions or the L858R point mutation in exon 21, are common in NSCLC. These mutations hyperactivate downstream signaling pathways, promoting uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival.

- Glioblastoma: EGFR amplification and mutations, such as EGFRvIII (a deletion mutant), are prevalent in glioblastomas. These alterations enhance tumor aggressiveness and resistance to therapies.

- Colorectal Cancer: EGFR overexpression is frequently observed and is associated with poor prognosis and treatment resistance.

These mutations highlight the critical role of EGFR in cancer biology and provide a rationale for developing targeted therapies.

Impact on Tumor Progression: Angiogenesis and Metastasis

EGF contributes significantly to tumor progression through its impact on angiogenesis and metastasis:

- Angiogenesis: Tumors require a blood supply to sustain their growth. EGF stimulates the production of angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promote the formation of new blood vessels. This enhanced vascularization allows tumors to access nutrients and oxygen, facilitating rapid growth.

- Metastasis: EGF signaling promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process where cancer cells lose their adhesion properties and gain migratory and invasive capabilities. This enables cancer cells to spread to distant organs, contributing to metastatic disease.

By hijacking these processes, tumors exploit the normal functions of EGF to support their growth and spread.

Targeted Therapies: EGFR Inhibitors

Given the central role of EGFR in cancer, targeted therapies have been developed to block its activity and suppress tumor growth. Two main categories of EGFR-targeted therapies are:

- Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs):

- Gefitinib and Erlotinib: Small molecules that bind to the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR, preventing phosphorylation and downstream signaling. These are particularly effective in NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations.

- Osimertinib: A third-generation TKI designed to target EGFR mutations, including the T790M resistance mutation.

- Monoclonal Antibodies:

- Cetuximab: A monoclonal antibody that binds to the extracellular domain of EGFR, blocking ligand binding and receptor activation. It is used to treat colorectal and head-and-neck cancers.

- Panitumumab: Another monoclonal antibody effective in EGFR-positive colorectal cancers.

Challenges: Despite their effectiveness, resistance to EGFR-targeted therapies often develops. Mechanisms of resistance include secondary EGFR mutations, activation of alternative signaling pathways (e.g., MET or HER2), and changes in tumor microenvironment.

EGF’s role in cancer biology underscores its importance as both a therapeutic target and a biomarker. Ongoing research focuses on improving existing therapies and developing novel strategies to overcome resistance, enhancing outcomes for cancer patients.

Therapeutic Applications and Future Directions

EGF in Regenerative Medicine: Applications in Wound Healing and Tissue Repair

Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) has significant therapeutic potential in regenerative medicine due to its role in stimulating cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Its applications include:

- Wound Healing: EGF-based creams and topical formulations are used to treat chronic wounds, burns, and diabetic ulcers. EGF promotes epithelial regeneration, enhances keratinocyte migration, and accelerates tissue repair.

- Tissue Repair: EGF is employed in tissue engineering and graft procedures to improve the healing of surgical wounds and damaged epithelial tissues, such as in corneal injuries.

- Cosmetic Applications: EGF is incorporated into anti-aging skincare products due to its ability to stimulate collagen production and skin regeneration, reducing wrinkles and improving skin elasticity.

Ongoing advancements in delivery methods, such as nanoformulations and hydrogels, aim to optimize the stability and efficacy of EGF in therapeutic settings.

EGFR Inhibitors: Current Drugs and Their Mechanisms

Targeted EGFR therapies have revolutionized the treatment of various cancers by disrupting EGF-mediated signaling pathways. Two major classes of EGFR inhibitors are:

- Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs):

- Gefitinib and Erlotinib: Bind to the ATP-binding site of the EGFR tyrosine kinase, preventing receptor autophosphorylation and downstream signaling.

- Osimertinib: A third-generation TKI designed to target both common EGFR mutations and the T790M resistance mutation in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

- Monoclonal Antibodies:

- Cetuximab and Panitumumab: Block EGF from binding to EGFR by targeting its extracellular domain. This prevents receptor activation and downstream oncogenic signaling.

These drugs have shown efficacy in treating cancers such as NSCLC, colorectal cancer, and head-and-neck cancers.

Challenges and Innovations: Overcoming Resistance to EGFR Therapies

While EGFR inhibitors have transformed cancer treatment, resistance to these therapies remains a significant challenge. Common mechanisms of resistance include:

- Secondary EGFR Mutations: Mutations like T790M or C797S confer resistance to first- and second-generation TKIs.

- Activation of Alternative Pathways: Tumors can bypass EGFR inhibition by activating parallel signaling pathways, such as MET or HER2.

- Tumor Heterogeneity: Genetic and epigenetic variability within tumors can lead to differential responses to EGFR-targeted therapies.

To address these challenges, researchers are exploring:

- Combination Therapies: Pairing EGFR inhibitors with drugs targeting alternative pathways (e.g., MET inhibitors).

- Bi-Specific Antibodies: Antibodies that target multiple growth factor receptors simultaneously to reduce pathway redundancy.

- Drug Delivery Innovations: Nano-drug formulations to improve the bioavailability and specificity of EGFR inhibitors.

Future Research: Novel Approaches Targeting EGF Pathways

The future of EGF-based therapies lies in harnessing cutting-edge technologies and novel approaches, including:

- Personalized Medicine: Genetic profiling of tumors to identify specific EGFR mutations and tailor therapies to individual patients.

- CRISPR-Based Gene Editing: Exploring CRISPR technology to correct EGFR mutations or disrupt aberrant signaling pathways in cancer cells.

- RNA-Based Therapeutics: Developing small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or antisense oligonucleotides to suppress EGFR expression in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy Integration: Combining EGFR inhibitors with immune checkpoint inhibitors to enhance anti-tumor immunity.

Emerging research also focuses on leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) to identify novel drug targets and design more effective EGFR-based therapies. These advancements hold promise for improving outcomes in cancer treatment and regenerative medicine.

Conclusion

Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) plays a pivotal role in cellular processes, from tissue regeneration to cancer progression. Its therapeutic applications, particularly in cancer treatment and regenerative medicine, highlight its clinical significance. While EGFR-targeted therapies have revolutionized cancer care, challenges such as drug resistance call for innovative approaches. Advancements in personalized medicine, gene editing, and combination therapies offer hope for overcoming these obstacles and unlocking the full potential of EGF in improving human health.

FAQ About Epidermal Growth Factor

Is EGF good for skin?

Yes, Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) is beneficial for the skin. It promotes cell regeneration, enhances collagen production, and accelerates the healing of wounds and damaged skin. EGF is commonly used in skincare products to improve skin elasticity, reduce wrinkles, and promote overall skin rejuvenation. It is particularly effective in treating signs of aging and repairing skin after injuries or cosmetic procedures.

What is the main function of EGFR?

The main function of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) is to regulate cell growth, survival, and differentiation. When EGF binds to EGFR, it activates signaling pathways that control critical cellular processes, including cell division, wound healing, and tissue regeneration. EGFR is also involved in processes like angiogenesis (blood vessel formation) and immune regulation, making it a crucial receptor in normal cellular functions and disease development, particularly cancer.

Which cells produce EGF?

EGF is primarily produced by a variety of cells in the body, including epithelial cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, and platelets. These cells release EGF in response to certain stimuli, such as tissue injury or inflammation. EGF is especially abundant in the skin, where it plays a key role in wound healing and epithelial regeneration.

What does the term epidermal growth factor refer to?

Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) refers to a protein that stimulates the growth and proliferation of cells, particularly in the epidermis (the outer layer of the skin). It was initially identified for its ability to promote the growth of epidermal cells, but its role extends to various tissues in the body. EGF binds to the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), triggering signaling pathways that regulate cell division, differentiation, and tissue repair.